Festivals and Parades

© 2020 Hannah Clayborn All Rights Reserved

|

Special celebrations marking the seasons have been a part of every society. Ancient seasonal festivals of Europe and the British Isles still influence the timing of some modern Christian holidays, conveniently spaced near equinoxes and solstices. Even our July Fourth holiday, seemingly the accidental birthdate of a nation, had the good sense to position itself near the height of summer.

The first people in these verdant valleys along what we now call the Russian River, the Pomo, Wappo, and perhaps other tribes, waited out centuries of wet winters in brush dwellings and semi-subterranean sweat houses. In the "World Sleeping Time" (winter) activity and travel slowed, leaving long hours for basket making and story telling. Such activities brought spiritual, social, and ceremonial renewal in dim smoky intimacy around a fire. Each cold, damp week brought them closer to "World Becoming New - Budding Out Time" (spring). With the warm weather came the "First Fruits" ceremony, honoring the new foods of spring. A special leader blessed these life-sustaining plants and then the people danced and ate in celebration.(1) Like the earliest springtime revelers here, the first white settlers also rejoiced at the passing of winter. May Day Chivalry

Although it eventually drew thousands of out-of-town spectators, the unique spring event first held in Healdsburg in 1857, was originally intended for the enjoyment of the town’s 100 to 200 residents. Roderick Matheson almost certainly instigated the first Healdsburg May Day Festival and Knighthood Tournament. It began the year he moved here from San Francisco, and it was held on the part of Matheson's property now known as Oak Mound Cemetery. Under the gnarled arms of ancient oaks, local store owners, smithies, and barkeeps donned the regalia and imagined names of medieval knights. These "Knights for a Day" tried their best to capture wooden rings with the point of a seven-foot lance while galloping at full speed. Meant to approximate the skills needed for real jousting, this sport was referred to as "tilting". No May Day would be complete without a flower-bedecked Queen of course. Miss Mary Jane Mulgrew, eldest daughter of the local blacksmith, reigned as the very first Queen of the May.(2) The early Healdsburg Knighthood Tournament was truly unique in California at that time. It was an outgrowth of a Nineteenth Century fascination with a mostly idealized vision of medieval chivalry and romance in Europe and the British Isles. Roderick Matheson, an educated immigrant from Kilearnan By, Tor, near Inverness Scotland, had probably read Sir Walter Scott's novels, like Ivanhoe, and was familiar with the Scottish aristocrats of the Waverly novels that also became popular throughout the United States. Roderick was born in 1824 in a classic medieval fortress known as Redcastle, where his parents were servants. Roderick would have been a teenager in 1839 when the famous Eglinton Tournament was held in Scotland about 190 miles from his home. Archibald Montgomerie, 13th Earl of Eglinton, nearly bankrupted his family by putting on a three-day reenactment of a medieval joust in full chivalric regalia that rivaled Woodstock in its catastrophic impact. The first two days of the tournament were rained out and no provisions for food or shelter had been planned for the 100,000 visitors. But on the third day the sun shone and the armored aristocrats staged a muddy melee that must have delighted the stalwart fans. Many distinguished visitors took part, including Prince Louis Napoleon, the future Emperor of France. Young Roderick was sure to have heard about it if he did not attend himself. The Matheson family left Scotland for New York the next year.(3) After four years of spring knighthood tournaments and events, May Day tilting in Healdsburg disappeared for a time. In its last year, 1860, there was an engraved invitation to a picnic at University Park, probably where the old Russian River Institute stood on University Street (then called the Agricultural and Mechanical University of California). Matheson was instrumental in founding that school and also taught there. In 1860 the May Queen was crowned by the chief justice, and a choir sang a May Day ode, after which the queen made her melodic reply. A royal banquet followed the day's events.(4) Roderick Matheson left Healdsburg for Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration in 1861 and returned in a coffin, as he was killed in 1862 while serving as a colonel in the Union Army. Those spring days spent in celebration under his massive oaks were remembered fondly in one of Matheson’s last letters home to his wife Netty from the Civil War battlefields. (see Col. Roderick Nicol Matheson on this site) Healdsburg's May Day Knighthood Tournament was probably inspired by the Eglinton Tournament, held in Scotland in 1839. The scenes above depict that event, which drew 100,000 visitors.

First County Fair

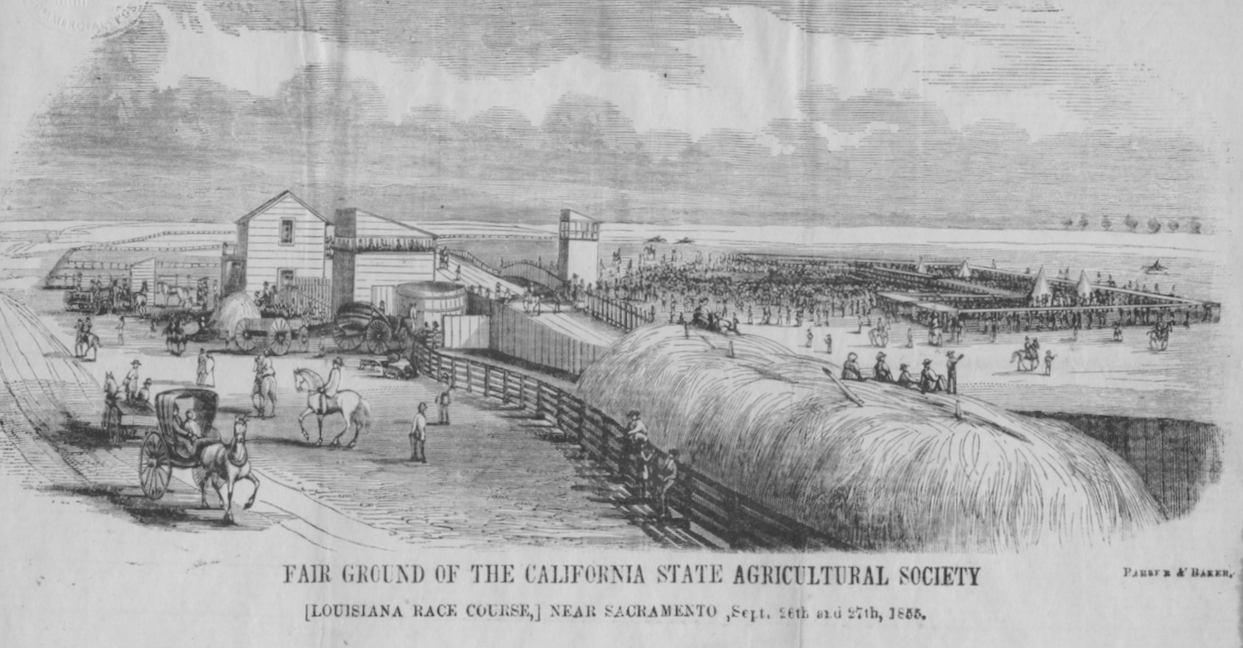

The May Day Knighthood Tournament was destined to return in its full glory in 1877, but in the interim there were events of a "more serious nature" at a location that would later become the Healdsburg Railroad Depot. W.P. Ewing, who bought a tract of land from Harmon Heald, hosted that first agricultural fair in Sonoma County in September 1859. It was called the Agricultural and Mechanics' Society Fair, so undoubtedly it was an enterprise involving the school on University Street, described above, and Matheson was also on the Fair Society’s Board of Directors. A reporter from San Francisco attended the event, describing in detail the oak-shaded fairgrounds and spacious pavilion, claiming that there were 4,000 fairgoers. There were so many visitors in fact that he had to share a hotel room that night. Aside from the many exhibits of fruits, vegetables, and grains, there were needlework, cooking, and woodworking entries, just like our modern fairs. Exhibitions of wild horse riding, horse races, and shooting matches added to the excitement. There were so many winners in so many categories, that it seems almost every farmer or rancher must have brought home a prize. The first prize for corn meal that year went to Hassett's Flour Mill, and considering it was the only mill in the area, not a long shot. One old-timer, J.S. Williams, remembered that first fair and thought it a great success, with many visitors from around the county and region. Williams reported that the local Indian population attended in force, and that the townsfolk at the time were mostly Missourians. Since it was so well attended by those in the surrounding towns and counties, this could certainly be called the first County Fair. There was a supper that evening for visitors, and a tar barrel was lit on fire on West Street to illuminate a political debate. But by then many had gone back to the Fair pavilion for the Ball, with dancing that apparently lasted all night long. According to Thompson's 1877 Sonoma County Atlas: The Sonoma and Marin Agricultural and Mechanical Society was organized and held its first fair in Healdsburg, in September, 1859. The second fair was held in Petaluma, in 1860; the third in Santa Rosa, September 24, 1861; the fourth in Sonoma, October 7, 1862. The name was changed to the San Pablo District Agricultural Society, and the fifth fair was held at Sonoma, September 15, 1863. The sixth fair was held at Napa, October 11, 1864. After that the society seems to have entirely collapsed. On the 6th of June, 1867, the Sonoma and Marin District Agricultural Society was organized, and was from the start a success. I believe this is the same Sonoma-Marin County Fair that exists today, held in Petaluma. Ewing, who also raised hogs and racehorses, had developed the first mill and resort at the Geysers. As stated in the same history: … In 1854 Major Ewing erected a cloth house where the present hotel stands. Like his friend Matheson, Ewing died during the Civil War, but fighting for the cause of the Confederacy, perhaps with the rank of Major.(5) Thus the Civil War stole away two of Healdsburg’s most innovative and enterprising early citizens and each died fighting for what he believed. The Sonoma and Marin Agricultural and Mechanics' Society would have emulated agricultural fairs like the one above, held near Sacramento in 1855. (UCB, Bancroft Library)

The Knights Ride Again

Seventeen years elapsed before the May Day Knighthood Tournament was resurrected. Because the 1877 event was nearly identical to the earlier May Day, it was certainly brought back by those who remembered it. But local newspaper reporters thought it was entirely unique to their own era, and were breathlessly pleased with the result. This later event was co-sponsored by the County Grange. At nine in the morning May 1, 1877, the crowd gathered in front of Powell's Theater (near the southeast corner of Matheson and Center Streets). There all 25 aspiring lancers had the Order of Knighthood conferred upon them by King Godfrey (on other days known as attorney and local political kingpin, L.A. Norton), clad in glittering crown and ermine cape and mounted on a coal black charger. Norton had traveled all the way to San Francisco to order appropriate costumes for the principal players. The Grand Marshall, with rosy sash and feathered chapeau on a snowy white charger came next. The 25 knights assumed new identities such as Prince Baldwin of Lorraine or Duke Narbona of France, taking an honored place behind the Healdsburg Band to lead the May Day procession. Next came the local judges and City Trustees, the major fraternal orders, the Volunteer Fire Company, the entire student body of the local public school, horsemen and volunteer "guards", assorted decorated carriages, and finally, the pedestrian rabble—or what little remained of the population of Healdsburg and outlying towns not already on the march. Soul-stirring strains from the band accompanied this impressive train as it continued on a parade route along Center to North, and then to Fitch, cutting a left to Piper and then to the main street, then called West. The procession made its way back to South (Matheson) for the final leg of the journey to the Tilting Grounds. As the original 1857 jousting site had become Oak Mound Cemetery by 1877, the Tilting Tournament took place nearby, on part of the old Matheson estate then known as Matheson Field. The County Grange tried hard to fit their own speakers and events into the program, but they were cut short due to the excitement of the tilting going on simultaneously—not to mention the lavish picnic lunch described by a reporter: …Then came the hour for lunch, and the rush for the baskets and booths. Ice cream, lemonade, and the creamy lager flowed in torrents. Hams, turkeys, chickens, cakes, pickles, jells and jams, were spread under the trees; and rapidly disappeared. At 1 o'clock, the tilting began in earnest, and, continued till about half past four, the most excellent horsemanship and graceful riding being displayed. It was reported that over 5,000 people attended the Tilting Tournament, where colorfully costumed riders in tasseled helmets and glistening armor tried to impale as many wooden rings as possible with a lance during a 100-yard dash after the peal of a bugle sounded. A single round of 25 rides occupied from 20 to 30 minutes. The triumphant knights in 1877 were Prince Raymond (Charles Brumfield) and Prince Otho (George Seawell). The five knights with the highest number of rings to their credit crowned the May Queen, Miss Jennie Johnson and her attendants. The banquet was held in the storeroom next to the regular dining room of the Union Hotel on West Street (now Healdsburg Ave.), which had been gotten up with gas chandeliers that brilliantly lit a repast of 14 turkeys and dozens of chickens. Later that evening Powell's Theater was the site of the Coronation Ball.(6) After such an extravaganza, it is understandable that 1878 was a breather year before the next blow out in 1879. But the young horsemen of Alexander Valley could not contain their Renaissance Fever, so they put on their own May Day knighthood tournament and picnic at Mr. Warren’s place by the bridge. That was followed by an evening dance of course.(7) The preparations for May Day 1879 started in March with meetings at the Sotoyome House hotel. Once again major community players, attorney L.A. Norton, entrepreneur Ransom Powell, and banker R.H. Warfield were involved. The winning program consisted of conferring Knighthood on 22 riders, a parade, band concert, orations, knighthood tournament, basket picnic lunch, May Queen Coronation, and a performance by a troupe of "Calithumpians" was to be augmented by a chariot race, hurdles, foot races, and a shooting tournament. Once again a grand ball ended the evening. The parade route was shortened, starting at Powell’s Theater it proceeded along Center to North Street, left to West (Healdsburg Ave.), left again to South (Matheson) St. and then on to Matheson Park. This year, the successful Knights would select the Queen and four maids of honor. Tilting prizes ranged from $20 to $5. The big day was attended by journalists from as far away as Sacramento, who reported that Petaluman Fred Kuhnle took away the $65 rifle, the top prize for shooting , and that Healdsburg’s own Sir Lanvol, Harry (Harrison) Truitt, was top knight. The reason for holding the spectacle was expressed by the local newspaper: ...Our people are now ripe for another grand celebration—we want something to infuse new life into the community, to bring together the populations of town, country and neighboring cities and villages.(8) But the grand effort could not be sustained annually. May Day 1880 consisted primarily of a rifle shooting tournament for county marksmen held at the Charles Alexander Ranch southwest of Healdsburg and a baseball game between the Santa Rosa "Amateurs" and the Healdsburg team, who got trounced. The traditional dinner was hosted at the Sotoyome House and a dance put on by Robert Powell.(9) Programs for the May Day Knighthood Tournament from 1877 (Russian River Flag) and 1879 (Healdsburg Enterprise).

Medieval Calithumpians: a spontaneous clown parade after a public hanging. Medieval Calithumpians: a spontaneous clown parade after a public hanging.

Calithumpians and Squeedunks

1870s May Day celebrations were enlivened by the performance of the Calithumpians, a large and rowdy group of performers whose main purpose was to satirize and lampoon all of the other participants and proceedings. Here is one definition I found: According to the Thamesford [Ontario] Calithumpian website, the word Calithumpian is an old English expression that is defined as a spontaneous clown parade or a party held after a public hanging…(11 May 2017 Woodstock Sentinel-Review) The first mention of California Calithumpians I find is in 1850 in Yuba City, where they appear to be a group of young men making prodigious amounts of racket with pots and pans and any handy noisemaker to celebrate a friend’s wedding. The word appears occasionally until 1873, when the San Jose newspaper reports that people from Castroville refer to their hoodlums (a term that originated in San Francisco) as Calithumpians. During the next few years Calithumpians turn up in Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, and Humboldt before making their entrance in Healdsburg in 1877. There were more Calithumpian Knights than real tilting knights, and they were described with more studious detail by one local reporter, who listed each of their names, like Prince Tanbark, Prince Take 'Em, Prince Useless, Prince End-over-End, and the Duke de Guerneville. The May Queen and her Court had counterparts in the Calithumpian Realm, all cross-dressing men with names like Miss Katrina Von der beer barrel. One reporter gave us a description of their performance, identifying it as THE BURLESQUE, a more familiar term: At the close of the tilt the Calithumpians, "25 Kings led by a Knight," made their appearance upon the scene. They wore the most comical costumes, were mounted upon fiery, untamed steeds ranging in age from thirty years upwards. At the sound of their bugle (a tin horn fourteen feet long), mounted in telescope fashion upon an ancient wagon which represented a chariot of old, the kings assembled to obey the commands of their knight. The rings, five feet in diameter, were suspended from the same arches where but a few minutes before the two-inch rings had been taken with lances, and the riders with unwieldy pikes proceeded to gather them in, to the great delight of the spectators, whose cheers together with the din of the tin horns, bull fiddles and other instruments of the Calithumpian band, made one imagine that he had been suddenly transported from the sportive fields of the chivalric Knights to the interminable turmoil of kings in the dominion of Old Nick…The costumes provided by these gentlemen for their kings were altogether original and strikingly in contrast with the very handsome and showy outfits provided for King Godfrey and his Knights by a San Francisco costumer.(10) Another form of the same burlesque performers were the Squeedunks who appeared locally in the 1880s. H.L. Menken in his book, The American Language, lists Squedunk as a term for backwater places, along with Podunk, Hohokus, and Hard-scrabble. Squeedunks were men (and in later years women) dressed in ridiculous or horrible costumes riding ridiculous or horrible vehicles. According to local historian, William Shipley, such Squeedunk Parades, or "grotesque pageants," used to come at the end of Independence Day celebrations as far back as the 1880's. He remembers his parents talking about such things in even earlier years (perhaps referring to the Calithumpians). According to Shipley the Squeedunks were meant to shock or frighten the citizenry, especially the children. Revived by William Miller in the 1920's these Squeedunk parades remained popular for many years.(11) Santa Rosa historians trace their Squeedunks back to the national centennial celebration in 1876. Following a long rambling speech in Spanish by General Vallejo, the County's first citizen, ...a band of masked men in outrageous costumes mounted the speaker's stand and explained their presence in the same stentorian voice adopted by General Vallejo. 'One hundred years ago today,' they intoned, 'the booming of the patriotic cannon awaked from their heroic slumbers a band of ancient Squeduncques. I have spotted the Santa Rosa Squeduncques a bit earlier, participating in the 1874 and 1875 Independence Day festivities. In the former year they are described as a … distinguished band of imps, devils, patriotic hoodlums and screechers…(12) The Squeedunks spoofed the patriotic puffery of the annual July Fourth programs, mocking every aspect of it, from a band that played on hat racks and garden hoses to the election of a queen and her attendants from the ranks of their least attractive male members. Squeedunks probably did not originate in Santa Rosa or Healdsburg. I suspect that the cynicism and lingering bitterness of Confederate sympathizers may have initiated it in the late 1860s. Thereafter its delightful irreverence made it a counterbalancing fixture in the pompous pageantry. Floral Festivals: Commercials for California

After a hiatus of nine years, the cyclical celebratory mood seized Healdsburg in 1888. Enough time had elapsed that once again some newspaper reporters had entirely forgotten its antecedents, as one proclaimed: A Novel Celebration. The citizens of this place are arranging to have a novel May Day celebration. The feature will be a Knighthood tournament, twenty-eight armored and mounted Knights competing. The winning Knight will crown the May Queen.(13) But this year as they prepared for the traditional tournament and festivities it was suggested that the ladies add a Floral Festival. I am surprised to discover that this 1888 floral festival actually preceded Pasadena’s famous Tournament of Roses (1890) and nearby Santa Rosa’s Rose Parade (1894). The earliest Floral Parade of consequence in California had been held in 1884 in Los Angeles, so it was not completely novel, but avante-garde nonetheless.(14) All the old favorites were back in form including the Calithumpians. Harry Truitt hadn’t lost his mojo and as Sir Lancelot took first prize in the Tilting Tournament again, while his brother, R.K. Truitt took the prize for Santa Rosa. The magic number of 5,000 guests thronged the streets. The 1888 event and its floral element had impressive coverage in Los Angeles and San Bernadino, so I like to think it might have started the Pasadenans down the floral path and would explain their use of the word "Tournament", which in Healdsburg had been used since 1857 to refer to the tilting.(15) The next major event was in 1893 and the reason for the partying intermission might have been the cost, as it was announced in April of that year that the money to defray the cost of the May Day event had been raised. The rest of the program remained the same, but dancing on a smooth temporary platform to the music of the Sotoyome Band was its main focus.(16) The innovations really took off in a three-day extravaganza in 1895, as described by a San Francisco paper: …The Healdsburg floral festival, baby show and riding tournament will be a success! If any doubt was entertained as to this, it has been swept away in the past few days by the enthusiasm that is being shown on all sides. It will not be a Healdsburg show. It will be a Sonoma County flower festival, held in Healdsburg, one of the most solidly prosperous towns in the interior.(17) Once again the Tribune reported, …not less than 5,000 people packed the sidewalks and looked from the windows, and porches, and awnings, or stood upon the housetops fronting the beautiful square.(18) The Plaza and downtown decorators chose a color theme of blue and gold and the procession was a mile long. Another reporter remarked on the enthusiasm of the 3,000 inhabitants of Healdsburg, and heralded their efforts to make the first floral festival a success, although we know it was at least the second if not third such show. As one reporter noted as the opening day dawned: …The incoming trains were all crowded—many even coming in freight cabooses—and great crowds arrived in carriages, buggies, carts, wagons and every other variety of vehicle ever known, while many came on horseback, an army on bicycles, and even not a few on squaw-back—for a decided feature is the dusky aboriginal. Never was Healdsburg’s hospitality, which is something proverbial, put to so severe a test as it is in this event. And never was hospitality in any town manifested in more lavish degree. Every citizen seems to have constituted himself a reception committee of one dozen to see to it that all visitors are made welcome—and made comfortable. An illustration of the foregoing feature: In front of the Enterprise office is suspended a huge sign, beautifully painted in carnival colors, and in letters which can be read clear across the plaza, bearing this legend: VISITING editors: THIS OFFICE BELONGS TO YOU !(19) Although 10 armor-clad knights still figured in the event, they were somewhat constrained on a cordoned-off track along Center Street. Their grandeur now seemed eclipsed by the brilliance of the ornately decorated coronation carriage bearing Queen Emma Meiler and her maids of honor, drawn by four white-plumed horses. The parade on the second day featured many other decorated carriages and floats, as well as beribboned bicyclists and costumed riders. One clever float, by Joe McMinn featured a cover of greenery framing a small orchard of cherry trees. Four lovely "summer" girls stripped the fruit from the trees as they rolled along, tossing it to the crowd. The inexhaustible supply of fruit came from containers hidden beneath their feet. The floral show itself was on the first night and was held in a transformed Truitt’s Theatre on Center Street, where, …the floral exhibition is beautiful beyond description. Immense quantities of the rarest and choicest flowers, potted plants, delicate trailing vines, ferns, evergreen boughs, etc, arranged with the best of taste, make the auditorium appear like a scene depicted in the Arabian Nights. A long program of musical entertainment included a novel whistling solo by Miss Helen Smith. The baby show was next with a ballot to pick the winner from 200 contestants, Irene Kelly won with 105 votes. The shortened course of the knighthood tournament on Center Street followed, and finally a band concert on the Plaza. The parade the next day was followed by a series of bicycle races, foot races, a pony race by Captain Charley’s Solano Indian riders, a tug-of-war between married and single men, a baseball game between Healdsburg and Forestville teams (final score 29–4), an evening opera featuring Anita Fitch de Grant, and 60 local girls performed the closing ceremonies after a final evening’s entertainment of music, recitations and tableaux.(20) The real purpose of this pageant and others like it could be seen in the parade float entitled "New England". Beside a miniature cottage, an unfortunate man lay half buried in a high snowdrift (made of cotton). On another, labeled "California", bowers of ferns, fruits, and flowers surrounded a serenely smiling child. Sheer entertainment was always a happy byproduct of such spectacles, but Promotion (with a capital "P", and that rhymes with "C", and that stands for "Commercial") was the main purpose of such gala pageants. The civic and commercial motives of the event might be guessed from the makeup of its executive committee, which included the largest fruit processor (James Miller), a bank president (George Warfield), owners of the largest retail firms (J. Gunn, A.W. Garrett), the owner of the most popular saloon (S. Hilgerloh), and the editor of the local Enterprise newspaper ( J. J. Livernash).(21) That doesn't mean it wasn't loads of fun. Many people stayed over for the three-day event, filling the local hotels and guest rooms to capacity and fulfilling the fondest hopes of local shopkeepers. Tonight the City is in the full flood of hilarity. The Plaza is brilliantly illuminated and crowds throng the street. enthused the Tribune as it described the first night’s outdoor entertainment on the plaza and a moonlight picnic beneath ancient gnarled oaks at the old tilting grounds on Matheson Street. The next year the event, now simply called a Floral Festival, was duplicated with all its many events, and was festooned in finery: The city is transformed. Healdsburg is fair enough in everyday dress, hot in her carnival braveries she seems drenched with rainbows. The streets are avenues of brilliant color. The arches of olive, gold and blue which span the streets relieve the heavier sweep of the flowing draperies, which look like flocks of bright-winged butterflies. All the stores and buildings have blossomed out, until a glance around the plaza gives the impression of a grove decked in festal array, as in the days when the great god Pan was worshipped and troops of nymphs and fauns held high carnival under the trees. People of every race and color have assembled here as candidates for citizenship in the cosmopolitan realm of gaiety. People from San Francisco, Petaluma, Cloverdale and Santa Rosa.(22) Unfortunately, at its height in 1896, the Healdsburg Floral Festival was taking second place to the coverage of Santa Rosa’s Rose Parade, which had now come into its own. That might explain why the knighthood tournament and floral parade migrated to July Fourth at the turn of the century. The May Queen had no trouble transforming into the Goddess of Liberty, and the show went on as before with the addition of fireworks, political and patriotic orations, a fire company hose competition, and the Squeedunks, who stood in for the beloved Calithumpians.(23) Like King Arthur, and his Round Table, the gallant Knights of Healdsburg faded into the mists of history, and the last mention I can find of the knighthood tournament is 1897, although other later sightings were reported. My guess is that the demise of tilting had two reasons. The town itself was running out of open land to have such riding competitions, which is why the last ones were staged in Alexander Valley. The other is that there were probably fewer citizens with the expert riding skills needed for tilting. The last floral parade, referred to as a Rose Carnival, was in 1904, when Isabel Victoria Simi reigned as its Queen.(24) An unfortunate footnote to Miss Simi’s coronation was an unsigned article and poem that appeared in the Windsor Herald, penned by editor Ande Nowlin, who accused Healdsburgers of being "a bunch of anarchists." Nowlin also claimed they were angry about the election of a "swarthy Dago", Queen Isabel. Another young businessman, Charles Crawford, who was crowned King Rex was accused of either being a "Dago or a Turk". This was a reference to the Immigration Act of 1903 (also called the Anarchist Exclusion Act). Outraged Healdsburg citizens burned Ande Knowlin in effigy on May 30, 1904, on West St. outside the Sotoyome Hotel. As practiced festival planners, this effigy-burning took place after a parade involving 150 or more prominent local citizens, and they saved Ande’s effigy head (a cabbage) and hat for another cremation the next day. Isabel Simi would later that year take over management of Simi Winery, after the sudden death of her uncle Pietro, likely from pneumonia on July 19, and her father, Giuseppi, after a long illness on August 13. She married Fred Haigh and became the legendary matriarch of Simi Winery, living to the age of 95.(25) Read articles, Burned Nowlin's Effigy in Public, May 30, 1904, and Ande Nowlin Cremated June 2, 1904. Assets of Floral Festival Liquidated

It was just about this time that the automobile began to appear, replacing equestrian romance with the wonder of the internal combustion engine. This innovation might have factored into the "liquidation" of the floral festival into the Healdsburg Water Carnival.(26) After 1901 an increasing number of people purchased automobiles of their own. The Russian River had always been a popular destination for resort-bound city dwellers who came by stage and train. Now with an automobile at their disposal, more and more Bay Area families flocked to the Russian River, for vacations and weekend recreation, staying not in the downtown hotels, but at local resorts like Riverside Villas or Camp Rose. After migrating to Fourth of July to avoid competition with Santa Rosa’s Rose Parade, Healdsburg’s midsummer heat would have made the riverbank a much more appealing venue than a dusty downtown. The appearance of Lake Sotoyome (now Memorial Beach) below the bridge, created by the seasonal dam, was also a perfect location to hold water sport competitions. The Russian River Fiesta, later known as the Water Carnival, was born in 1905, the year following the last Floral Festival. On August 15 and 16, 1908, it was a full-scale summer splash spectacular featuring a water pageant with enormous decorated floats (and they did). Although the first water carnivals did not draw the same attendance as the best of the Healdsburg Floral Festivals (referred to in the newspaper as "land carnivals"), the 1908 event drew many thousands to the banks of the river. There were a few familiar features: the inevitable Queen and her attendants, a parade down to the banks of the river, and a grand ball to close the event. Other new attractions included diving exhibitions from the top of the Railroad Bridge by the Olympic Club of San Francisco, and fireworks by the banks of the moonlit water. The floats, unhindered by the friction of land travel, grew immense. Predictably the winning float made good advertising copy, a golden barge bearing a maiden representing the fair State of California. Its beauty inspired one reporter to versify: Soft the crystal waves divided, While a rainbow arch abided, On its canvas' golden fold. But it was Ed Snook's truly monstrous floating swan that captured the imagination of the crowd.(27) Despite its picturesque popularity, the water carnival did not appear again until 1913, and then took another leave of absence until 1925. The problem was the expense of the show and a lack of sponsors. The previous festivals were funded primarily by local businessmen and hoteliers who benefitted from the downtown crowds.(28) Favorite of the Pioneers: Independence Day

Although there is no record of the first community celebrations of the earliest American and European settlers in northern Sonoma County, it is a good guess that Independence Day played a large role. The accounts of immigrants on the trail and in the new towns and cities of California record many Independence Day celebrations. The earliest July Fourth celebration recorded in Healdsburg was in 1858. When the Hassett Brothers built their new flour mill near the southeast corner of the current Healdsburg Avenue and Matheson Streets in June of that year, it was the largest building in town. Before the steam-driven mill machinery arrived, the cavernous structure held a gala Independence Day Ball. Organizers included John and Aaron Hassett, entrepreneur Ransom Powell, Squatter Captain Dr. Elisha Ely of Geyserville, storekeeper George H. Peterson and other leading citizens. Tickets, including the price of supper, cost $5.00, a significant sum in those days.(29) The next Healdsburg Independence Day celebration recorded, in 1866, teetered with a precarious balance between factions that had so recently fought a bloody Civil War. Although an estimated 2,000 people from the North County turned out to hear poetry, patriotic oration, eat potluck, and witness the pyrotechnics, the local newspaper fretted, ...we entertained fears lest some indiscretion on the part of our leading citizens might cause an estrangement rather than a union of sympathies on the occasion. The same sort of program came off the next year, but this time hosted by Windsor residents, (known as "People of the Big Plains") at the Guilford School grounds. After the railroad united most of the towns of the county, the main Independence Day celebration traveled about, one year in Santa Rosa, the next in Petaluma, and the next in Healdsburg.(30) In 1897, as we have noted, the July 4th celebration merged with the Floral Festival, transforming the May Queen into the Goddess of Liberty and her numerous beguiling attendants added sauce to the spectacle of the usual parade. Independence Day dominated local celebrations from about 1897 to about 1935, focused primarily on the Russian River from 1905 on. The zenith of its popularity came in 1925 and 1926, when reported crowds of 15,000 attended.(31) Four years passed without an event before it reappeared in 1931 with water sports (relay races, diving contests, and motorboat racing) and other competitive games, including twilight baseball and the Fitch Mountain Marathon, took the foreground in 1931 and 1932. These were probably much less expensive than the spectacular water pageants during the lingering economic stranglehold of the Great Depression. (32) Harvest Festival

The Russian River Festival returned in a new season and with a new name. Beginning in 1937 the Healdsburg Harvest Festival, staged over Labor Day to attract thousands of Bay Area, Redwood Empire, and county residents, moved to the fore. Several familiar features—a Labor Day parade, queen contest, coronation ball, water sports, fireworks display, and the Fitch Mountain Marathon—-assure us that this "new event" was simply repackaged and repositioned for maximum tourist impact. (33) The Harvest Festival had a good run until World War II. The old river floats attained a certain type of immortality in 1943 when they and the Russian River appeared in two motion pictures, Happy Land and The Five Sullivans, both with wartime themes. In exchange the Chamber of Commerce got $25 for their postwar celebration in 1946. The next year, 1947, was the last event for many years, as it was advertised that the Healdsburg Harvest Festival, which cost $10,000 to stage, finished $690 in the hole. It took several non-celebratory years of indecision before the Chamber of Commerce made the official decree to abandon it in 1950. One of the problems, noted the Chamber, was that the main supporters of the event, the prune, grape, and hop growers, were just too busy with their own harvest at that time to participate. (34) Prune Blossom Tour and Wine Festivals

On the occasion of the Prune Blossom Tour's 15th birthday, the local newspaper recounted the history of the Prune Blossom Tour: Healdsburg has had many crops over the years, but the prune dates to 1846 when Cyrus Alexander first planted trees in the valley that now bears his name. The trees took hold, many more were planted over the years, and soon Healdsburg became the buckle of the prune belt. The combination of prune blossoms, mustard, green-green grass and fresh country air made a tour a natural idea…but was the brainchild of Mrs. Larry Carson, publicity chairman for the Healdsburg Chamber of Commerce in 1961…only 300 viewed the blossoms in 1961…the tour started at the chamber offices at 217 Healdsburg Ave., but by 1967, the beautiful Villa Chanticleer became the center of attraction. ..In 1963 the Russian River Farm Bureau served its first luncheon to 274 people. A thousand cookies were baked for visitors by 4-H Club members. In 1964 Healdsburg Arts presented its. first display of spring paintings. By the next year, 1,500 visitors from 19 states and seven foreign countries were making the tour. Among the guests were 40 who flew into Healdsburg’s Municipal Airport. In 1966 the Prune Blossom Tour was selected as one of the top travel events in the United States for the month of March, the only California event chosen. Unfortunately, everything was in blossom that year but the prunes. No matter, 1,900 people enjoyed themselves. This year [1975] additional honors came to the Tour. Travel magazine listed it as one of the top 20 events in the world for the month of March…In 1969, the last year with Frank Zak as chairman, registration reached 2,440. The blossom tour reached its greatest growth in 1972 when 3,300 signed the registry at the Villa and another 2,236 lunches were served by the Farm Bureau. (35) Although grape vines had been a part of Healdsburg agriculture since its inception, an increasing emphasis on viticulture began to take a big toll on the prune orchards by1970. Reflecting that change, the Prune Blossom Tour changed to the Spring Blossom Tour in 1974, and then disappeared after 1975. The first annual Russian River May Wine Fest at Healdsburg, California was held May 13, 1972. (36) Back to the Future Farmer's Fair

A small fair was held about 1948 by the old American Legion Hall, on the west side of Center between North and Piper Streets. It was a tiny thing really, on a dusty lot, just for the Healdsburg kids who would be the Future Farmers of America. Like Healdsburg's first festival, it was held in May, for that was when the boys and girls neared promotion, graduation, and summer vacation. It sort of grew into a parade. The Future Farmer's Fair, now held at Giorgi Park, is very near the site of that first May Day Festival in 1857, held on the lot now called Oak Mound Cemetery. Back to the Future—Farmer’s Fair. Endnotes

1. Vera-Mae Fredrickson, Mihilakawna and Makahmo Pomo, People of Lake Sonoma, 27, 46. 2. W.A. Maxwell, "Early Healdsburg Memories" in Tribune 2 April, 1908, 1:3). "J.S. Williams Writes Reminiscently" in Enterprise, 14 Feb. 1914. 3. James M. McPherson, Ordeal by Fire; the Civil War and Reconstruction, 48. The Eglington Tournament 1839: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eglinton_Tournament_of_1839. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rqRTFDDNMUU. For more information about Roderick Matheson see Roderick N. Matheson: City Builder and Civil War Hero on this site. 4. Healdsburg Enterprise, Volume XLVIII, Number 2, 9 July 1925 (1 & 8). 5. Long article describing first Marin-Sonoma County Fair: Daily Alta California, Volume 11, Number 247, 6 September 1859(4). "J. S. Williams Writes Reminiscently," Healdsburg Enterprise, Volume XXXVIII, Number 28, 14 February 1914(1). Heald, The Heald Family, 29, 30. Russian River Recorder, Jan. 1977, 3. Account of J.S. Williams in Russian River Recorder, Oct. 1977, 3. Major Ewing and W.P. Ewing: Atlas Map of Sonoma County California, Thomas H. Thompson, Oakland: Thos. H. Thompson & Co. 17, 18, 20 1/2. 6. Handbill for Knighthood Tournament, May Day 1877, Healdsburg; Healdsburg Museum Archives. Russian River Flag, Volume IX, Number 21, 29 March 1877. Russian River Flag, Volume IX, Number 25, 26 April 1877(3). San Jose Mercury-news, Volume XI, Number 47, 5 May 1877. Russian River Flag, Volume IX, Number 26, 3 May 1877 (3). 7. Healdsburg Enterprise, Volume III, Number 12, 25 April 1878 (3). 8. Healdsburg Enterprise, Volume IV, Number 5, 6 March 1879 (3). Healdsburg Enterprise, Volume IV, Number 12, 24 April 1879 (3). Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 8, Number 51, 2 May 1879 (1). 9. Russian River Flag, Volume XII, Number 27, 6 May 1880(3). 10. Quote: Press Democrat, Volume IV, Number 77, 3 May 1877 (3). Russian River Flag, Volume IX, Number 26, 3 May 1877 (3). Daily Alta California, Volume 1, Number 85, 8 April 1850(2). San Jose Mercury-news, Volume III, Number 115, 23 July 1873(2). Morning Press, Santa Barbara, Volume III, Number 4, 6 July 1874. 11. Dr. William Shipley, Tales of Sonoma County, 136, 137. Henry Louis Mencken; The American Language, 4th ed., Knopf, 1962, p. 553. 12. Le Baron, Mitchell, et all, Santa Rosa: a Nineteenth Century Town, 151-153. Sonoma Democrat, Volume XVII, Number 38, 27 June 1874 (4). Russian River Flag, Volume VII, Number 35, 8 July 1875 (3). 13. Press Democrat, Volume XIV, Number 216, 21 March 1888 (2). 14. Healdsburg Enterprise, Volume XII, Number 43, 23 March 1888(3). Gaye LeBaron, Santa Rosa: A Nineteenth Century Town, 155. 15. Healdsburg Enterprise, Volume XII, Number 49, 2 May 1888 (3). Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Volume 1, Number 7, 2 May 1888. Los Angeles Herald, Volume 29, Number 171, 21 March 1888 (1). San Bernardino Daily Courier, Volume 3, Number 141, 24 March 1888 (2). 16. Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Volume 11, Number 4, 13 April 1893(3). 17. San Francisco Call, Volume 77, Number 154, 13 May 1895 (1). 18. Reprint of original article 17 May 1895 in Tribune 20 Aug. 1956. 19. Sonoma Democrat, Volume XXXVIII, Number 32, 18 May 1895 (3) 20. San Francisco Call, Volume 77, Number 154, 13 May 1895 (1). San Francisco Call 16 May 1895 (1). Sonoma Democrat, Volume XXXVIII, Number 32, 18 May 1895 (3). 21. Letterhead for Healdsburg Flower Festival, May 6-8, 1896, listing executive committee, Healdsburg Museum archives. 22. Sonoma Democrat, Volume XXXIX, Number 39, 9 May 1896 (5). 23. Sonoma Democrat, Volume XXXIX, Number 39, 9 May 1896 (5). Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Volume XVII, Number 12, 11 June 1896. San Francisco Call, Volume 82, Number 30, 30 June 1897. San Francisco Call, Volume 82, Number 34, 4 July 1897 (4). The Weekly Calistogian, Volume XX, Number 32, 9 July 1897. Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Volume XXIII, Number 11, 8 June 1899 (4). San Francisco Call, Volume 86, Number 33, 3 July 1899 (3). Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Volume XXIII, Number 15, 6 July 1899 (1). Press Democrat, Volume XLII, Number 79, 8 July 1899. 24. Floral Festival continues on July 4 until 1904. Marin County Tocsin, Volume 26, Number 13, 9 July 1904. 25. Cremation of Ande Nowlin: Press Democrat, Volume XXX, Number 127, 31 May 1904. Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Volume XXXII, Number 9, 2 June 1904(7). Quote "swarthy Dago": Healdsburg Museum Curator Holly Hoods, as quoted: https://patch.com/california/healdsburg/history-more-than-twisted-at-healdsburg-museum. Death of Giuseppi and Pietro Simi: Healdsburg Enterprise, Volume XXIX, Number 7, 23 July 1904(4). Press Democrat, Volume XXX, Number 196, 19 August 1904(3). Sotoyome Scimitar, Volume 7, Number 23, 24 August 1904. San Francisco Call, Volume 96, Number 89, 28 August 1904(34). Isabel Victoria Simi Haigh, findagrave.com. 26. Enterprise 8 May 1889; 26 March, 16 April, 7 & 14 May 1904. Tribune 9& 16 May 1895; weekly 19 March to 14 May 1896. Handbill advertising Healdsburg Flower Festival, May 26-28, 1904, Healdsburg Museum Archives. 27. Press Democrat, Volume XXXI, Number 254, 15 October 1905 (1). Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Volume XVIII, Number 24, 6 September 1906 (1). Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Volume XIX, Number 16, 11 July 1907 (1). Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Volume XX, Number 22, 20 August 1908. Healdsburg Tribune 16, 23, 30 July, 13 & 20 Aug. 1908, 28 May, 4, 11, 25 June, 2 July 1909. Press Democrat, Volume XXXV, Number 149, 27 June 1909 (5). 28. No carnival was held in 1910 (Venetian Carnival in Monte Rio); no carnival 1911, 1912, 1914, 1915, 1916, 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924. Healdsburg Enterprise, Volume XXXVII, Number 51, 12 July 1913. Healdsburg Enterprise, Volume XLVIII, Number 2, 9 July 1925 (1 & 8). 29. W.A. Maxwell, "Early Healdsburg Memories", in Healdsburg Tribune, 26 March 1908, 1:5 & 4:5. 30. Democratic Standard, 11 July 1866 (2:1); 11 July 1867, 3:1. Gaye LeBaron, Santa Rosa: A Nineteenth Century Town, 151, 31. Democratic Standard 11 July 1866 (2:1) Russian River Flag 3 June and 1 July 1869, 3:3 & 4:1; 7 July 1870, 3:1. Healdsburg Tribune, 1 July 1897. Knighthood Tournament: Enterprise 27 June 1903, 1:1. Healdsburg Tribune 20 June 1907, 1:1. Enterprise 9 July 1925 (1:6). Sotoyome Scimitar, Volume XXII, Number 77, 6 July 1926 (1); 23 June 1932, 6:2. 32. Healdsburg Tribune 2 July 1909. Programs for the 1913 (July 3-5) and 1931 (June 20,21) Russian River Festivals, Healdsburg Museum Archives. no carnival 1927, 1928, 1929, 1930. Healdsburg Tribune, Number 53, 6 January 1931. Sotoyome Scimitar, Volume 33, Number 10, 18 June 1931 Edition 02 (1). Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Volume LIV, Number 43, 21 April 1932 (1). Oakland Tribune, Volume 116, Number 114, 23 April 1932 (5). No carnival 1933, 1934, 1935, 1936. 33. Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Volume LXXIV, Number 84, 8 September 1938 (1). Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Volume LXXIV, Number 97, 3 August 1939 (1). Tribune, Diamond Jubilee Edition, 26 Aug. 1940, 68. Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Volume LXXVI, Number 95, 28 August 1941. Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Volume LXXVI, Number 97, 4 September 1941 (4). 34. Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Volume LXXIX, Number 3, 22 October 1943 (6). Geyserville Press, Number 49, 6 September 1946 (1). Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Number 50, 12 September 1947 (1). Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Number 50, 12 September 1947 (2). Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Number 32, 5 May 1950. 35. quote: Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Number 39, 20 March 1975. 36. Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar, Number 39, 23 March 1972. |